A Spotlight on Khmer Boxing

I've

just come to the end of an extremely enjoyable project with Emmanuèle

Phuon and Amrita Performing Arts, collaborating as sound designer / composer for Brodal Serei (Freestyle Boxing). This work was inspired by the life of professional Cambodian boxer Hem Saran and recently showed at Esplanade's da:ns festival 2016, Singapore.

"Brodal Serei... examines the

personal history and lives of the Khmer boxer beyond the thrills and

spills of the boxing ring in present-day Cambodia. Weaving dance, drama

and storytelling, Emmanuèle Phuon’s latest work is an intimate portrayal

of the fighter’s psyche and way of living.

Dancers of Amrita

Performing Arts embody the masculine and rugged energy of fighters,

with choreography inspired by fight movements, physical regimes and the

rituals of Khmer boxing. Brodal Serei casts a spotlight on the mind and

body of the Cambodian boxer, and the success and struggle of a cultural

form where economy and sport are intertwined intricately." – Brodal Serei (freestyle boxing) programme for da:ns fest.

Background

The impetus for Brodal Serei (Freestyle Boxing) stemmed from an encounter Manou (Emmanuèle) had with photographer John Vink’s exhibition on Khmer boxing in Brussels 10 years ago.

The roots of Khmer boxing can be traced back to Bokator, an ancient Khmer fighting style used by the warriors of Angkor. Some say that the Angkorian empire was a force to be reckoned with, largely due to their deadly and versatile martial arts practise. Indeed the term Bokator translates to "pounding a lion". Perhaps one of the reasons why its modern day incarnation plays such a big part in Cambodian popular culture is because of its historical lineage.

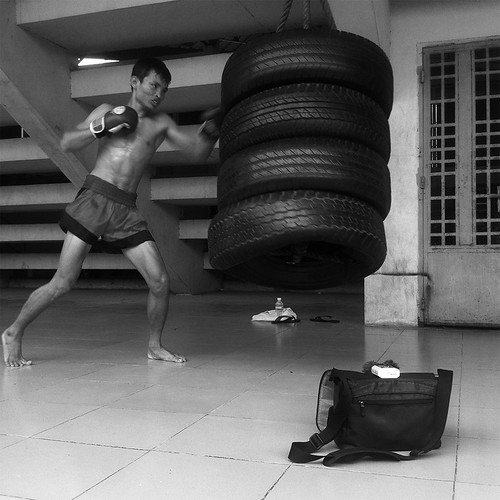

'Superfighter' Tou from Amrita, who has a background in martial arts, including Bokator

The impetus for Brodal Serei (Freestyle Boxing) stemmed from an encounter Manou (Emmanuèle) had with photographer John Vink’s exhibition on Khmer boxing in Brussels 10 years ago.

"The images were startling, not only because of the violence made

evident by sweat, straining muscles, battered faces, and the powerful and beautiful bodies locked

in embrace, but because of the additional stark desolateness of the settings: parking lots, bodies

falling directly on dirt, car tires and canisters filled with sand as props. These photographs were

taken during training sessions as well as boxing matches. In every one of them, the spirit of

Cambodia was tangible—a mixture of poverty, good humour, hope, cruelty and superstition." – Manou Phuon

Manou took the initial steps of this project with Amrita back in 2014. During this time, she befriended professional boxer Hem Saran, who she invited to collaborate on the project. He began to teach the rudiments of boxing to her and Amrita dancers Tou, Rady and Mo, illuminating the movements and mentality of his practise.

"...they threw themselves into the fight experience, learning to move and dance in sometimes counter-intuitive ways compared to their dance training. As they worked with Emmanuèle, the dancers of Brodal Serei slowly crafted a story of Hem Saran. At the same time, a parallel story of movement is always present: the story of the Amrita dancers with their able bodies and artful physicalities that reveal their own training and art as they tell Saran’s story. At the end, two strands of stories, of artists and athlete, with multiple threads of movements and choreographies, of fight and art, become a singular tale of life and strife." – Lim How Ngean (dramaturg for Brodal Serei)

In the above video you can hear two of the compositions I created during the first phase of my involvement. The first track 'Superfighter' would later be revised. As I wrote to Manou before we began phase two:

"Although the rhythm and tempo work well with your choreography here, I feel there is not enough tension in the sound composition and the musical progression is too linear. Basically, I think the energy of the sound / music could compliment the energy and progression of the movement more effectively if it had a bit more dynamics and texture.

I would rework what I have created, but expand the palette of sounds I use to include field recordings from a boxing match, and transformed srilai sounds... I'm reminded of the idea we spoke about early on about what the boxer hears when they are fighting or training hard... maybe we can play with this idea here, and create a kind of internal / impressionistic soundscape of sorts."

To which she replied:

"All good, it is a collaboration: you need to be happy with what you do! ;-)"

I arrived to the first event a bit late, so I only caught the last two fights. A cacophony of bellowing voices criss-crossed the arena, some directed at the fighters and others towards the bookies they placed bets with! I spotted a guy who had created a one-man DIY call-centre of sorts; an A3-size board with 20+ mobile phones from a decade ago secured to its surface, which he proceed to speak into one by one, occasionally placing his ear against them. I couldn't quite work out if he was taking bets over the phone, or just relaying the action to those who couldn't be present!

One thing that struck me was the 'interlude music' booming across the tall speaker stacks between rounds. Above the chattering voices and tense atmosphere, this cheeky / cheesy little number somehow took the edge off things (for me at least). That said, apparently a fight kicked off within the crowd just moments after we left after the final match! A few bets turned sour, I guess.

The second event was more

interesting. I arrived early, an hour before the event started. The

ring was dark, the camera crane was limp, and the fans had yet to arrive. The vast space felt raw and rough around the edges; the cold concrete floor, the rugged metal seating, the exposed steel supporting beams, all setting a pre-emptive tone within this theatre of masculinty.

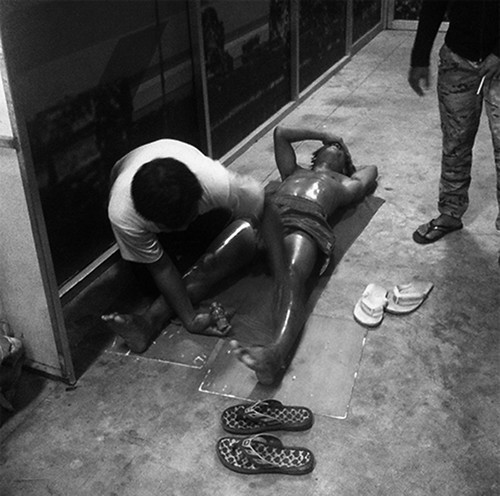

Through

Saran I was able to spend some time 'backstage' with the fighters as they prepared

for their fights. We encountered Saran’s friend who was having a pre-fight

rub down with some Tiger Balm-esque oil. The pungent aroma of

camphor and eucalyptus filled the room. He seemed relaxed and he didn’t

mind me taking pictures. I noticed he was missing a toe.

In the ring matey seemed nervous. He barely threw a punch or landed a kick. The crowd pointed and jeered at him. He spent all three rounds defending himself against his opponent. He looked afraid. Both his coach and Saran were highly critical of his performance. He was shouted at between rounds, and eventually lost the match. After the fight he was teased and taunted, but he 'took it like a man'.

Another Khmer boxer started his fight at the other end of the confidence spectrum. He went full-steam ahead from the bell with his signature roundhouse-kick-followed-by-spinning-punch combo! The audience were going berserk and baying for a knockout. With his fans behind him he got his opponent on the floor. A primal soundscape brimming with brash voices engulfed the arena. As crowd-pleasing as his performance was, he lost on points. However he left the venue with a quiet smile on his face and a box of the sponsor's whisky in hand, which he distributed amongst his friends.

Being a spectator in this overtly masculine environment was as fascinating as it was uncomfortable for me. I've never truly been at ease with the stereotypically macho end of 'maleness'. Perhaps because I exist outside of its heavily ring-fenced boundaries, whenever I see its codes and conventions acted out, it feels so performative.

The sounds that fill the boxing arena envelop the listener in an atmosphere of masculinity, setting the stage for its performance and projection; the desire for dominance, the display of alpha, the admiration of strength and bravado, the hero narrative.

However, as much as this environment hold up a mirror of machismo, it also reflects ideas of respect, rigour, ritual, fear, friendship and fragility: These boxers are hard men, but beneath their tough exteriors lie instability and uncertainty. The economics of the sport set against the backdrop of modernisation in Phnom Penh, can sometimes mean they literally fight for survival.

Manou's vision was to manifest an experience of this reality on stage, by synthesising movement, music and narrative, and uncovering the poetry in-between.

Tou & Rady clinching in rehearsal

Manou took the initial steps of this project with Amrita back in 2014. During this time, she befriended professional boxer Hem Saran, who she invited to collaborate on the project. He began to teach the rudiments of boxing to her and Amrita dancers Tou, Rady and Mo, illuminating the movements and mentality of his practise.

"...they threw themselves into the fight experience, learning to move and dance in sometimes counter-intuitive ways compared to their dance training. As they worked with Emmanuèle, the dancers of Brodal Serei slowly crafted a story of Hem Saran. At the same time, a parallel story of movement is always present: the story of the Amrita dancers with their able bodies and artful physicalities that reveal their own training and art as they tell Saran’s story. At the end, two strands of stories, of artists and athlete, with multiple threads of movements and choreographies, of fight and art, become a singular tale of life and strife." – Lim How Ngean (dramaturg for Brodal Serei)

I was invited into this project in 2015, after being introduced to Manou by How Ngean. At this point the structure of the piece was taking shape and Manou had some ideas of how sound design & music could work in certain scenes. She shared these ideas and some video footage of the scenes, so I could start to develop some sketches in response to the intention and choreography therein.

In addition to this, Manou had made audio recordings of Saran talking about his life experiences as a boxer, which were to play an important role within the work. These recordings needed some attention in terms of audible clarity – i.e. reducing background noise and reverb, and removing unwanted artifacts of speech (coughs, clicks, bass thuds). Izotope's RX5 was perfect for this particular job!

So, I hastily got to work creating and 'cleaning' what I could audio-wise, before setting off to Phnom Penh to meet the team. It was a short and intensive week refining what we could before the 'work-in-progress' showing back in Dec 2015.

Excerpt from Brodal Serei @ 1:30–3:00

Excerpt from Brodal Serei @ 1:30–3:00

In the above video you can hear two of the compositions I created during the first phase of my involvement. The first track 'Superfighter' would later be revised. As I wrote to Manou before we began phase two:

"Although the rhythm and tempo work well with your choreography here, I feel there is not enough tension in the sound composition and the musical progression is too linear. Basically, I think the energy of the sound / music could compliment the energy and progression of the movement more effectively if it had a bit more dynamics and texture.

I would rework what I have created, but expand the palette of sounds I use to include field recordings from a boxing match, and transformed srilai sounds... I'm reminded of the idea we spoke about early on about what the boxer hears when they are fighting or training hard... maybe we can play with this idea here, and create a kind of internal / impressionistic soundscape of sorts."

To which she replied:

"All good, it is a collaboration: you need to be happy with what you do! ;-)"

Chinese construction in Phnom Penh

Fast-forward 9 months and I'm back in Phnom Penh. The work has been commissioned by Esplanade and with their support we now have the means to bring the work to the next level. In order to 'level up' the sound design my first duty was to become closer to the subject matter and get a feel for of the kind of aural environments Saran worked in.

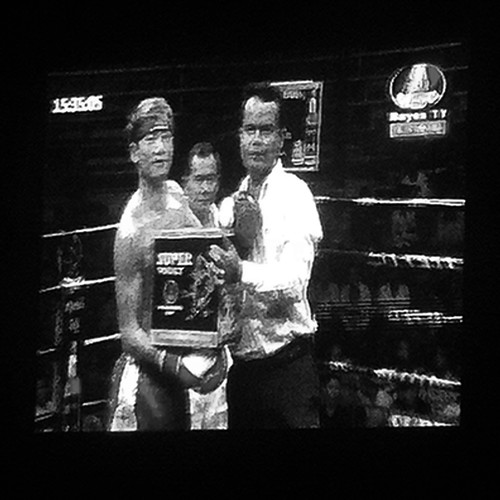

Hem Saran VS Sok Chenda

So, I spent most of my time making field recordings at different locations around this colourful and chaotic city; from the guttural cheers of fans at the matches...

...to the explosive grunts, thumps and rhythms of

boxers training at the Old Stadium...

So, I spent most of my time making field recordings at different locations around this colourful and chaotic city; from the guttural cheers of fans at the matches...

...and the grungy cafes where old fellas

watch the fight, play chess and drink coffee thick with condensed milk.

Theatre of Masculinity

I went to two boxing matches whilst in Phnom Penh, kindly guided there by Borey from Amrita. Both fights were held at local TV stations. These were big warehouse / industrial spaces

rigged with lights, cameras, tiered seating and full of eager fans, mostly comprised of local men and teenagers, ever-ready to spectate and bet on the fights to ensue.

I arrived to the first event a bit late, so I only caught the last two fights. A cacophony of bellowing voices criss-crossed the arena, some directed at the fighters and others towards the bookies they placed bets with! I spotted a guy who had created a one-man DIY call-centre of sorts; an A3-size board with 20+ mobile phones from a decade ago secured to its surface, which he proceed to speak into one by one, occasionally placing his ear against them. I couldn't quite work out if he was taking bets over the phone, or just relaying the action to those who couldn't be present!

Interlude music with announcer @ 1:54–2:22

One thing that struck me was the 'interlude music' booming across the tall speaker stacks between rounds. Above the chattering voices and tense atmosphere, this cheeky / cheesy little number somehow took the edge off things (for me at least). That said, apparently a fight kicked off within the crowd just moments after we left after the final match! A few bets turned sour, I guess.

In the ring matey seemed nervous. He barely threw a punch or landed a kick. The crowd pointed and jeered at him. He spent all three rounds defending himself against his opponent. He looked afraid. Both his coach and Saran were highly critical of his performance. He was shouted at between rounds, and eventually lost the match. After the fight he was teased and taunted, but he 'took it like a man'.

Another Khmer boxer started his fight at the other end of the confidence spectrum. He went full-steam ahead from the bell with his signature roundhouse-kick-followed-by-spinning-punch combo! The audience were going berserk and baying for a knockout. With his fans behind him he got his opponent on the floor. A primal soundscape brimming with brash voices engulfed the arena. As crowd-pleasing as his performance was, he lost on points. However he left the venue with a quiet smile on his face and a box of the sponsor's whisky in hand, which he distributed amongst his friends.

Being a spectator in this overtly masculine environment was as fascinating as it was uncomfortable for me. I've never truly been at ease with the stereotypically macho end of 'maleness'. Perhaps because I exist outside of its heavily ring-fenced boundaries, whenever I see its codes and conventions acted out, it feels so performative.

The sounds that fill the boxing arena envelop the listener in an atmosphere of masculinity, setting the stage for its performance and projection; the desire for dominance, the display of alpha, the admiration of strength and bravado, the hero narrative.

However, as much as this environment hold up a mirror of machismo, it also reflects ideas of respect, rigour, ritual, fear, friendship and fragility: These boxers are hard men, but beneath their tough exteriors lie instability and uncertainty. The economics of the sport set against the backdrop of modernisation in Phnom Penh, can sometimes mean they literally fight for survival.

Collaborative Process

Initially Manou and I worked separately, or rather in parallel, only meeting when we were at an important juncture or in need of assessing something together in situ. She entrusted me to follow my own creative process within this project; whether gathering material outside or working on it alone at home / hotel, I felt I had the space to explore and develop ideas with autonomy.

Clinching duets at the Old Stadium

I think this approach worked mostly because I had the time to get to know the work (during my first trip to Phnom Penh), experience the subject matter first hand (during my second trip) and perhaps most importantly, become friends with Manou and understanding her artistically! Our process was also helped along by the fact that we share some overlap in our creative approach; once the subject is rooted and material germinates from it, we both enjoy working instinctively with the material to see how it can grow.

Leaving room to 'play' with materials in such a way is something that excites us both, since it can sometimes lead to outcomes that may never have been reached purely through rationality. We both attribute this to the idea that our respective mediums are like languages in their own right and thus spoken / written language can at times distort or miscommunicate what can be expressed through body or sound. Hence, its important for us to give some primacy to our mediums.

That's why whenever we discussed potential ideas for the sound, I would try my best to describe it and Manou would reply "Great! Let’s try it!" or "Sure – show me what you mean!".

Sound can be quiet abstract and intangible to most people, unless you're someone that works with it directly or interacts with it often. If you're not familiar with ways sound can be ‘shaped’ then describing how a sound can transform may be hard to hear in the minds ear; for example, using words to describe "an insect-like abstraction of a whistle with a sharp crescendo and sudden transformation into an actual whistle, which in turn reveals the scene" – might be not be easy to conjure before audition.

Whistle-abstraction transition in Boxing Club / Training scene @ 0:00–0:15

So, upon returning to SG from my second stint in Phnom Penh, I spent my days at rehearsals testing out ideas in the rehearsal studio, and my evenings at home tweaking, editing, reviewing, and generating more ideas to try out the following day.

Arrangements, Boundaries & Contours

There was a healthy variety of sound material to find balance with in relation to the choreography and narrative of the piece; Khmer text (predominantly from Saran's interviews), English voice overs (from me), live traditional music (played by Amrita musicians Sopheap, Chanti and Nan), and my composed music and designed soundscapes.

Before I began phase two of the project, I revisited the documentation film of our first performance in Phnom Penh. One of the problems we had was that the scenes felt too bracketed, like a series of separate segments. Similarly, I felt the live traditional music and my compositions were like two different worlds at times.

There was a healthy variety of sound material to find balance with in relation to the choreography and narrative of the piece; Khmer text (predominantly from Saran's interviews), English voice overs (from me), live traditional music (played by Amrita musicians Sopheap, Chanti and Nan), and my composed music and designed soundscapes.

Before I began phase two of the project, I revisited the documentation film of our first performance in Phnom Penh. One of the problems we had was that the scenes felt too bracketed, like a series of separate segments. Similarly, I felt the live traditional music and my compositions were like two different worlds at times.

Chanti playing the srilai

To remedy these issues I sought relevant sounds to 'bleed' between scenes and smooth over the boundaries separating them. I recorded the Amrita musicians playing solo to resample as potential 'threads' to link scenes together, as well as to weave into my compositions where appropriate.

Still from our Phnom Penh dress-rehearsal

A simple illustration of this is after the 'Trio' scene. Sopheap strikes the 'mini gong' hard to signify the end of the live music, whereupon a recording of the mini gong smothered in reverb is cued.

Gong transition @ 1:00–1:25

This creates the illusion that the gong is still resonating, as the fighters fall to their knees exhausted. The gong helps to brings us out of the reality and intensity of the last scene with its energetic movement and live music, and gently glide the energy and pace downwards. The first gong hangs in a stasis accompanied by a thin sine tone mimicking 'ringing ears', before by a second gong appears softly and brings with it a quiet soundscape of bird song, followed by the voice of Saran talking about when he was young. To me the presence of the birds does two things here; (1) interacts with image of the tired boxers, dazed and on their knees – perhaps the birds could be circling their heads (in a slightly cartoonish manner); and (2) introduces us to a new environment where the narrative of Saran's childhood takes place.

Visual description of gong transition at the end of Trio

Being inside the work as a creator sometimes makes its hard to zoom out and see a wider view of its contours and overall composition. This is just one example of where our dramaturg How Ngean gave valuable insight and feedback. He identified a structural motif that we appeared to have been following; text, music, dance, text, music, dance... and repeat! Despite the little transitions between scenes I had created, this motif made the piece feel a bit predictable. So, we experimented with the arrangement of, for example, the text and sound / music for certain scenes.

Arrangement of elements for 'Selling fights' text into the start 'Superfighter' music

In tandem, I started to think more about how my other field recordings from around Phnom Penh could be integrated into some of the text to add subtle hints of texture and impressions of place.

Spatialisation

Before we got into the Esplanade Theatre Studio, where the piece was to be performed, I started thinking about spatialisation. I had planned to use a 4-channel set up to create an aural experience akin to surround sound and enhance the sense of space, place and movement within the piece. I made use of the 4-channel set up for most scenes, however, I think the best illustration of using it can be heard in the 'Boxers club / Training' scene.

Boxers Club / Training (montage) @ 0:00–1:00

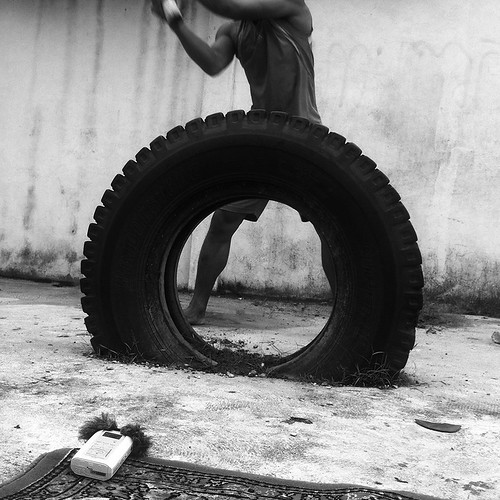

In this scene, which follows a nightmarish slow-motion fight, we see characters enter one by one and begin their training regimes – flipping a tyre, whacking a tyre, skipping, sit ups. These actions litter the scene with repetitive rhythmic sounds. As the musicians enter the soundscape begins to have more hints of colour and personality; Khmer voices fill the space with banter, the musicians warm up with their instruments, and the master conducts a movement / training sequence using short sharp rhythmic counting.

Saran demonstrating an exercise with baseball bat and tyre

The previous scene 'Nightmare' ends quietly and in total darkness. The aforementioned whistle-abstraction appears, evoking the image of an insect and creating a momentary link between the idea of night and the world of dreams, before a sharp crescendo reveals the real whistle and the scene unfolds around the audience.

Three main layers that comprise the background soundscape within Boxers Club / Training were; the 'road' (with many bikes, recorded outside of a boxing event), 'voices' of the boxers (chatting and getting refreshments on their break), and a distant 'top view' perspective (of all the boxers action).

My visual reference used to create an aural impression of the 'top view'

In treating these 3 layers I thought about how to create a sense of acoustic depth and subtle dynamics. For the ‘top view’ recording I EQ'd and applied a reverb effect at about 70% wet / 30% dry. These sounds were positioned on the effects speakers 3 + 4, at the sides of the audience. In contrast, the ‘voices’ were position at speakers 1 + 2 with reverb at 15% wet / 85% dry. Together this enhanced the depth perception of space; the audio from 3 + 4 create the illusion of listening to the scene from further away; whilst the audio from audio 1+2 is perceived as being a bit closer; and finally the acoustic action occurs just beyond.

Coverage of 3 layers (+ acoustic actions). Pink=Road, Light Orange=TopView, Grey=Voices

The bikes from the 'road' intermittently swelled in volume once per minute, creating waves of warm textures that would shift between different positions in the space (for example, from speakers 1+3 to 3+4 then onwards to 2+4. This created the effect of bikes appearing and slowly circling the space at different intervals.

At points in the scene when the overall sound was more sparse, I introduced soft looped rhythms which emerge out of the background sound. These subtle layers were designed to interact with the acoustic actions in different ways; sometimes as rhythmic counterpoint and other times as a means to draw quiet lines of dramatic tension between characters on stage.

Speaker panning / crossfade ideas, where 1–4 = speakers numbers

I also made use of space and movement with these looped sounds, panning them across speakers and bringing them into different reverberent spaces over time. This occasional overlaying of 'unreal' or impressionistic sounds served to contrast the realism of the scene, juxtaposing patterns of flurrying fists and bursts of breath on top the everyday mundanity before our eyes.

In terms of deciding what sounds to use for these 'unreal' moments, I first spent time preparing various audio clips recorded at the Old Stadium, which I would then improvise with live during rehearsals. After 5 or so runs of the scene, I realised that keeping things minimal and stripped down was the best way forward.

Indeed, after a certain point much of the process of refining the sound design / music within the work was to reduce and simplify, rather than head towards more complex or denser states. Taking a more minimal approach to composition can sometimes clarify affect and intention and potentially result in creating more space for the audience to 'move' within a work, in terms of perceiving and reading it.

Indeed, after a certain point much of the process of refining the sound design / music within the work was to reduce and simplify, rather than head towards more complex or denser states. Taking a more minimal approach to composition can sometimes clarify affect and intention and potentially result in creating more space for the audience to 'move' within a work, in terms of perceiving and reading it.

That's a wrap!

After such a creatively fulfilling and inspiring project I felt like there was a lot of experience to unpack, hence this tl;dr blogpost – kudos to you, if you made it all the way to the end! I am massively grateful to everyone who was part of production – thank you for a wonderful ride (and for putting up with my last minute ideas, perfectionist tendencies and occasional sonic tunnel vision).

I've come away from this project feeling very positive and harbouring a strong desire to further explore the possibilities of sound design and music for contemporary dance. Indeed I'm happy to say that I'll be going to New York this December to work with Manou during her Baryshnikov Arts Center residency...

♪ ♪ Start spreading the news! ♪ ♪

Esplanade Presents: Brodal Serei (freestyle boxing), programme booklet for da:ns fest 2016

http://www.fullcontactmartialarts.org/bokator-khmer.html

Credits

All images in the post were photographed, drawn or created by me. #narcissist